While we were paddling the shallow waters of Florida Bay, we learned things we expected to learn, like reams of information about the bay and the Everglades of which it is a part and names and details about the species after species of birds that we paddled past or that soared above us over the course of a 3-hour kayak.

We also learned things we never expected to learn on this little adventure and heard phrases we never expected to hear.

Like, for example, sharks are easy to flip.

We heard this sentence uttered by someone that not only knows this to be a fact, but has done it herself.

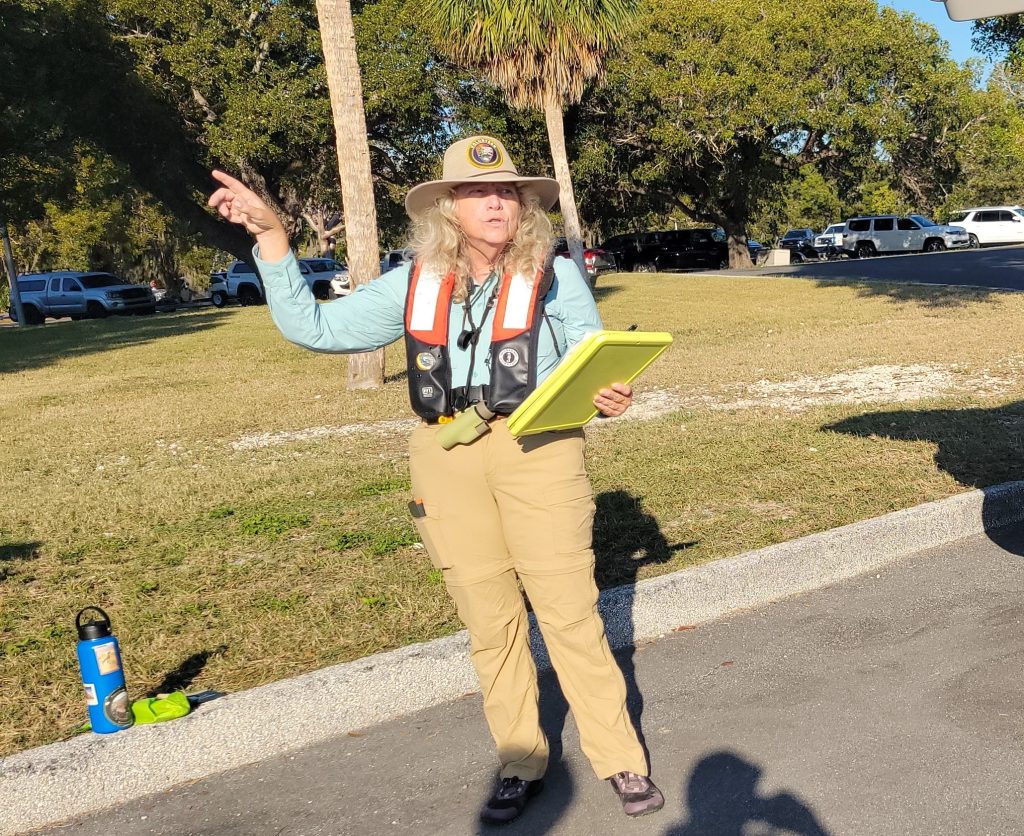

Meet Anita, the 10-year veteran park volunteer and “retired” wildlife biologist with stories to tell from all over this world and a near endless encyclopedia of knowledge about the biology and ecology around us. Anita had a wonderful and unique kind of way about her. She wore time and experience like it was a casual visitor that she didn’t expect to stay long and certainly wasn’t going to let get in her way as she led a three hour paddle excursion that left many people decades her junior struggling to keep up. She did have a faster boat than the rest of us, but she paddled it through the morning with the kind of ease that made it seem that no exertion was necessary. She spit out a near constant stream of information about the ecosystem we were paddling through and we worked hard to keep up with her so we could catch as many of her nuggets of wisdom as we could. She stopped 3 or 4 times throughout the trip so that everyone could catch up and hear the information that they otherwise would miss out on being as far back behind as most of the other paddlers were.

Anita had a gruff air about her that could easily make a meek person back down in intimidation rather than approach her or make an inquiry. That gruffness was more just an affect and an outgrowth of the type of no-nonsense approach that seems difficult to avoid when you have enough knowledge to navigate landscapes with confidence that others would back away from out of ignorance-induced fear. Despite that feeling that she gave off, each word that somewhat gruffly came out of her mouth was, in seeming contradiction, friendly, welcoming, encouraging and enthusiastically happy to engage and answer any questions. Thanks to us being determined to learn as much as we could from her, we paddled without intimidation from the water, her pace or any unintentional vibes she may have radiated. Boy are we glad we did.

As we paddled alongside her, not only did we find a wealth of information about the world we were floating through, we struck a goldmine of life experience and stories worth telling from a woman that had been diving for 50 years and whose career began and ended with her intimate involvement in the cleanup of 2 of the worst acute environmental disasters in US history, the Exxon Valdez oil spill and the Deepwater Horizon. These two terrible oil spills bookended her long and storied career and she had the stories to tell. We peppered her with questions, and she responded with abundant edification.

We learned how we have all been potential contributors to the clean up of oil spills. If you have ever sat in a chair in a salon and left piles of hair that was once on your head on the floor to be swept up, you may have helped to clean the ocean. That hair that is swept up is put in bags and shipped to a place that holds onto those bags and bags of human hair in case they are needed for such uses, being, along with cocoa fiber, one of the two most effective substances for cleaning up oil spills. We learned that, as long as the hair is cleaned and stripped of its own natural oils first, it is capable of absorbing multiple times its weight in oil. We learned that that is exactly what it did to remove the unbelievable amount of liquid black gold that was spilled into the ocean during those two incidents and that the hair was then cleaned for reuse. The oil that was removed from it was sent back into the pipeline for processing to its ultimate destination as fuel or whatever other destiny industry had for it.

We learned that there are different temperatures at which different types of oils liquify and there are certain oils that, if they spill into the ocean, are easier to clean up because they just turn into one big pile of jelly and others that require more effort.

We learned how devastating such events were to the ecosystems, not just in the ocean, not just around the ocean, but to the human ecosystems as well. There are fishermen whose businesses would be basically destroyed for the two years it would take for the ocean life to recover. If you remember the coverage from the Exxon Valdez of all of those wildlife biologists cleaning oil-soaked birds with Dawn Soap, one of those was probably Anita. She told us how there is no other soap that is as effective at cutting through harsh oils as Dawn and that is what they used. We learned how the Exxon Valdez clean up was made particularly difficult, not just because of the scale of the spill, but because of the cold and choppy Alaskan waters that made it difficult for humans to interface with it safely. Anita’s job at the Deepwater Horizon incident was with the Coast Guard and part of her job was to determine the amount of the fines that the companies would have to pay, not just to cover the cleanups, but to cover the fisheries whose livelihood they had just destroyed for the next couple of years.

We were rapt with attention, gathered around the campfire of her kayak, soaking up her knowledge and life experience and pinching ourselves that we just happened to be in the company of someone with so much of both to share.

It didn’t hurt that the setting was the beautiful waters of the bay and our “campfire” companions were white and brown pelicans dive bombing the water to fish for their breakfast and great white herons sailing around and past us as we took in her every word.

At one point a small shark swam between our two boats and our conversation turned to these incredible fish.

Don’t worry, it wasn’t a Steven Spielberg type of shark that was blood thirsty for human swimmers. We had no need for bigger boats.

It turns out, not all sharks are the type that you need to be terrified of, though for those of us who don’t know the difference, best to keep a healthy fear across the board. And, that said, we definitely needed to keep all body parts in the boat and we learned a bounty of important safety tips from Anita about what to do if you do find yourself accidentally in shark or alligator or crocodile infested waters. Well, it depends which waters and which sharks, crocodiles or alligators. But in this shallow bay we were in, we learned that, if you do accidentally end up in the water (because there is no reason for you to ever do it on purpose) the last thing you want to do is flail your limbs in panic. The water is not crystal clear like in some spots in Florida. It is muddy and murky and just like we can’t see the animals below the surface, they can’t much see us. But a flailing limb is slightly visible through the muck and looks an awful lot like a flapping fish. And the crocs that were in these waters, Anita informed us, were one-bite eaters. They were not the type to grab their prey and drag them down to the bottom of the water for later munching. They wanted to eat something they could get in one bite. None of the things in these waters have any interest to eat humans, but, a flailing human-leg-fish would be worth a test bite for sure. And Anita made it clear to us, though the crocodile’s strength to open their mouth was so weak a rubber band could easily keep them clamped shut, going the other direction, our meager human limbs were no match for the 3,000 pounds of pressure that would clamp down on them. She also made it clear that it was extremely easy to stay safe in this setting as long as you were not specifically seeking to, in her words, “compete for a Darwin Award”. There had only been four incidents where limbs were lost (but no lives lost) in as many decades and all of them had been a result of a human deciding to do something that a ranger had expressly told them not to do for their own safety. Human beings being as prone to idiocy as we all are, the Darwin awards, tragic though they may be, often have stiff competition.

While it is still advised to have a healthy fear of sharks, Anita told us some tales about some of the sharks for which no fear is necessary. One such shark very briefly showed itself later in the journey as it swam by Anita’s kayak, the lemon shark. Anita told us stories about being the adopted human for many a lemon shark over her years diving. It turns out, they love to have their bellies scratched by a human that is willing to pull the parasites off of them. If you happen to do that service for a lemon shark, you will get yourself a personal underwater bodyguard. The lemon shark is able to memorize the light and dark patterns of individual divers and Anita told us, when you go into the water, they will seek out their particular adopted human for parasite removal and belly rubs. Then, for the rest of your dive, they will swim a perimeter around you to protect you from barracudas and other more hungry sharks and sea life. This is clearly not an activity to do if you are not a person with the skills to do it, but Anita was one such person. Anita explained how the lemon shark will even play bouncer to other lemons, essentially saying, “this is my human, go find your own”.

Listening to Anita talk about her underwater and overwater adventures had us hanging on every word. She made it clear that there are ways to stay safe with sharks, just like anything else in the natural world with the proper amount of knowledge and understanding, respect for your environment and situational awareness. This is definitely one of the major lessons we’ve learned on this trip and is a great lesson to expand into life itself.

We then asked the question that we are sure is on other people’s minds as well.

“Once you actually run into a shark and have one swimming at you, is there anything you can do, or is it just game over?”

That’s when she said it and it landed on our ears like spaghetti getting thrown at a wall – sticky, wild and unexpected.

“Yes. You can flip a shark.”

We didn’t even know what that meant.

Well, it means exactly what it sounds like it means. You can flip a shark.

Well, she can, anyway.

After the brief moment where our brains temporarily stopped working like a record screeching to a halt, we inquired further.

As she continued that there were things to be done in such a scenario, she also made it clear that you have got to be experienced and know what you are doing if you have any hope of remaining fully intact. So, we don’t expect any readers of this to get out and start trying shark flipping for an afternoon of entertainment – got it? This is very much a “don’t try this at home” scenario.

“Well, sharks are neutrally buoyant, so they are easy to flip.” Anita said as casually as someone might say, “well, I’m hungry, want to go out for dinner?”. We nodded as if “neutrally buoyant” was a natural part of any conversation.

She continued, “Once they are on their back, they go catatonic.”

How convenient. That would have made Jaws a very different movie.

”Yea, you can flip a 2100 pound 12 foot shark with the twist of your hand.”

At this point, we were, as expected, agog.

”I know it can be done, because I’ve done it.”

Reference aforementioned agogness.

Usually, if someone is telling stories like this, you are likely to assume they are making it up. Cause, what? But Anita had the street cred, the knowledge and the official titles to back up these stories – at least for our satisfaction.

You can imagine how many questions we had now.

“What was that like? Experiencing that type of adrenaline in the moment?” Ryan asked.

Up until that point, Anita had been spilling out information that was eliciting all kinds of emotional responses from us without even the slightest falter in her voice that could have differentiated her from listing off the ingredients for her favorite pie recipe. This was the first moment she showed signs of the human emotions that were there the whole time, but were hard for us mere mortals to discern through the blanket of toughness that was just a natural part of her nature.

”I don’t want to think about it.” She said with a quick and curt measure of visceral exasperation that let us know, we may have just moved into “intrusive” territory with our curiosity.

”Oh gosh, we are sorry to have pushed you to talk about it,” we responded with regret for digging deeper than we should have, “I’ll stop asking questions.” Ryan said with an acknowledging chuckle as we both prepared to reign in our frothing inquisitiveness.

Well, it turns out this conversation was truly a volley and she just needed a moment to get through the surging memory. After a breath, without further inquiry from us, she carried on.

”It doesn’t hit you until hours later. In the moment, you are just in it. Then two hours later it hits you, like, whoa, what the hell just happened.”

We also learned how she ended up in that situation to begin with. This was the first time we heard words out of her mouth that matched the gruffness in her tone. Despite the fact that their boat had the signal up that there were divers in the water, a small fishing boat nearby had just been throwing their lunch debris overboard, turning the surrounding waters that had been filled with divers into a buffet for the local jaws. Anita, being the senior diver of that group, with the according responsibility to be the last out of the water, had put herself in front of a charging shark before her heroic (our words, not hers) shark-flipping skills came into use while her fellow divers cleared the water behind her. With one hand on the ladder, a tiger shark charged at her, and she put her one free hand up. When the tiger shark made it into her arm‘s reach, she grabbed its snout and, with a quick flip up her wrist, gave that shark the pancake flip of its life.

She told this story as casually as one might comment on tying their shoes. Ryan had to follow up to make sure we were really understanding what had happened.

”With one hand?”

”Yup.”

Well, those fishermen on that little boat that had thrown their lunches so cavalierly into the water did not have their own lemon shark putting up a perimeter around them to protect them from the wrath of Anita that was about to come at them for their thoughtless and situationally UNaware behavior. We are not sure even a lemon shark could stand up to the skill of an angry Anita. She was probably ready to dole out a Darwin Award of her own to those folks and we do not envy them the earful they surely received.

Well, the earful we received from Anita was as welcome as they come.

We left the Florida Bay waters with sunshine on our shoulders, greater knowledge and insight into the world of the sky and under the water and a tremendous respect for the people working hard to take care of the biological and ecological world around us and trying to protect it from us and us from it, despite the obstacles we, in all of our human flaws, put in their way in the process.

And, most of all, we left with gratitude and respect for Anita and we suggest everyone else do the same.

She can flip a shark.

Leave a comment